Now, the fun begins. If you followed my last post about the basics of DNS, you should be armed and ready to tackle the subject of this post: DNS enumeration.

DNS enumeration is the process of obtaining as much information about a target as possible by pulling from publicly available DNS records. This can expand the attack surface of a target by revealing their internet facing servers, email addresses, and more depending on how extensively you enumerate.

The keyword in this definition is “publicly“. That means that all of the methods I’m about to show you in the next section you can try on your own (and I encourage you to do so).

However, it’s important to note that some automated scripts brute-force subdomains by default, which may overload some older servers. This is unlikely though, but just make sure you know what the tool is going to do before you fire it off.

With that being said, let’s get into enumerating DNS!

Manual Techniques

There are several scripts out there that allow you to automatically scrape tons of DNS information in a point and click fashion. However, it’s important to know how to manually enumerate DNS in order to modularize enumeration and adapt it to more specific situations.

Don’t let the term “manual” scare you though. I’m going to go over a few tools that will make this process a snap.

Whois

Using the Whois service is a great starting point in your quest for information. With just the domain name of a target’s website, you can pull it’s registrar information, geographic location of its servers, name servers associated with it, and contact information system admins and technical support.

The whois command is built into most UNIX based operating systems. So, if you’re running one of it’s variants like a Linux distro or MacOS, you can run:

whois <domain name>You’ll quickly be overwhelmed with a bunch of information about that domain name. For this reason, I recommend using an online tool like https://www.whois.com/whois. They organize data a bit more graphically than the plain terminal-based whois command does.

DiG

If there’s one manual tool you need to know, it’s the dig command. Like whois, it comes prepackaged with many UNIX variants. Unlike whois, it’s much more powerful.

To use dig, follow this format:

dig @<name server> <domain name> <record type>The name server and record type positional arguments are optional. You can use dig in the same way as you would whois:

[~]$ dig github.com

; <<>> DiG 9.16.1-Ubuntu <<>> github.com

;; global options: +cmd

;; Got answer:

;; ->>HEADER<<- opcode: QUERY, status: NOERROR, id: 4266

;; flags: qr ra; QUERY: 1, ANSWER: 1, AUTHORITY: 0, ADDITIONAL: 0

;; QUESTION SECTION:

;github.com. IN A

;; ANSWER SECTION:

github.com. 60 IN A 192.30.255.113

;; Query time: 115 msec

;; SERVER: 8.8.8.8#53(8.8.8.8)

;; WHEN: Tue Feb 28 19:17:22 PST 2023

;; MSG SIZE rcvd: 44By default, dig pulls A records and uses whatever nameserver it can access from my /etc/resolv.conf file. As you can see, it decided to use Google’s nameserver at 8.8.8.8.

Of course, dig can be used for so much more. Let’s try pulling the nameservers of github.com:

[~]$ dig github.com NS +short

dns1.p08.nsone.net.

dns2.p08.nsone.net.

dns3.p08.nsone.net.

dns4.p08.nsone.net.

ns-1283.awsdns-32.org.

ns-1707.awsdns-21.co.uk.

ns-421.awsdns-52.com.

ns-520.awsdns-01.net.In this example, I told dig to grab me the NS records associated with github.com and keep the output short and sweet with the +short query modifier. I like to use +short with dig because the output can be pretty cluttered.

Another useful query type is the ANY query, which pulls all available records associated with a domain:

[~]$ dig github.com ANY +noall +answer

github.com. 60 IN A 192.30.255.113

github.com. 900 IN NS dns1.p08.nsone.net.

github.com. 900 IN NS dns2.p08.nsone.net.

github.com. 900 IN NS dns3.p08.nsone.net.

github.com. 900 IN NS dns4.p08.nsone.net.

github.com. 900 IN NS ns-1283.awsdns-32.org.

github.com. 900 IN NS ns-1707.awsdns-21.co.uk.

github.com. 900 IN NS ns-421.awsdns-52.com.

github.com. 900 IN NS ns-520.awsdns-01.net.

github.com. 900 IN SOA ns-1707.awsdns-21.co.uk. awsdns-hostmaster.amazon.com. 1 7200 900 1209600 86400

github.com. 3600 IN MX 1 aspmx.l.google.com.

github.com. 3600 IN MX 10 alt3.aspmx.l.google.com.

github.com. 3600 IN MX 10 alt4.aspmx.l.google.com.

github.com. 3600 IN MX 5 alt1.aspmx.l.google.com.

github.com. 3600 IN MX 5 alt2.aspmx.l.google.com.

...As you can see, dig was able to pull a variety of records, including SOA and MX. I also used the +noall combined with +answer query modifiers to single out the responses in the output. This is useful if you just want to see the results of a query (no annoying header messages) but want a little more info than what’s provided with +short.

Additionally, dig can initiate zone transfer. A zone transfer is the process DNS servers use to transfer copies of records of a particular zone to another server. This is primarily used for redunancy–if one server goes down, another server with copies of all the records will be able to resume operation in its place.

Misconfigured servers allow zone transfers to occur between anyone that requests it (including you). This can potentially leak private records.

With dig it’s as simple as:

[~]$ dig @dns3.p08.nsone.net github.com AXFR +noall +answer

; Transfer failed.I used the AXFR query type to initiate a zone transfer with one of github.com‘s nameservers. It didn’t let me. Good job GitHub.

This is usually the case as zone transfers are a well-known vulnerability. However, never rule them out. Company nameservers usually have multiple nameservers for redundancy. In some cases, backups might be overlooked in terms of hardening. So, try zone transfers against all of a target’s nameservers. You might get lucky.

Host

Another tool worth mentioning that is very similar to dig and is bundled with most UNIX-based OS’s is host. Keep in mind this is not the same host command that is available on Windows by default.

Just typing host and supplying it a domain name can reveal some useful information:

[~]$ host reddit.com

reddit.com has address 151.101.129.140

reddit.com has address 151.101.193.140

reddit.com has address 151.101.1.140

reddit.com has address 151.101.65.140

reddit.com has IPv6 address 2a04:4e42::396

reddit.com has IPv6 address 2a04:4e42:600::396

reddit.com has IPv6 address 2a04:4e42:400::396

reddit.com has IPv6 address 2a04:4e42:200::396

reddit.com mail is handled by 5 alt2.aspmx.l.google.com.

reddit.com mail is handled by 1 aspmx.l.google.com.

reddit.com mail is handled by 10 aspmx2.googlemail.com.

reddit.com mail is handled by 10 aspmx3.googlemail.com.

reddit.com mail is handled by 5 alt1.aspmx.l.google.com.With just one argument, host was able to pull reddit.com‘s A, AAAA, and MX records in an arguably cleaner fashion than dig.

A useful argument I like using when running host is a:

[~]$ host -a reddit.com

Trying "reddit.com"

Trying "reddit.com"

;; ->>HEADER<<- opcode: QUERY, status: NOERROR, id: 12601

;; flags: qr rd ra; QUERY: 1, ANSWER: 34, AUTHORITY: 0, ADDITIONAL: 0

;; QUESTION SECTION:

;reddit.com. IN ANY

;; ANSWER SECTION:

reddit.com. 278 IN A 151.101.193.140

reddit.com. 278 IN A 151.101.129.140

reddit.com. 278 IN A 151.101.65.140

reddit.com. 278 IN A 151.101.1.140

reddit.com. 86378 IN NS ns-557.awsdns-05.net.

reddit.com. 86378 IN NS ns-1029.awsdns-00.org.

reddit.com. 86378 IN NS ns-1887.awsdns-43.co.uk.

reddit.com. 86378 IN NS ns-378.awsdns-47.com.

reddit.com. 878 IN SOA ns-557.awsdns-05.net. awsdns-hostmaster.amazon.com. 1 7200 900 1209600 86400

reddit.com. 278 IN MX 5 alt2.aspmx.l.google.com.

reddit.com. 278 IN MX 1 aspmx.l.google.com.

reddit.com. 278 IN MX 10 aspmx2.googlemail.com.

reddit.com. 278 IN MX 10 aspmx3.googlemail.com.

reddit.com. 278 IN MX 5 alt1.aspmx.l.google.com.

reddit.com. 3578 IN TXT "google-site-verification=zZHozYbAJmSLOMG4OjQFoHiVqkxtdgvyBzsE7wUGFiw"

reddit.com. 3578 IN TXT "logmein-verification-code=1e307fc8-361a-4e39-8012-ed0873b06668"

reddit.com. 3578 IN TXT "onetrust-domain-verification=6b98ba3dd087405399bbf45b6cbdcd37"

reddit.com. 3578 IN TXT "stripe-verification=9bd70dd1884421b47f596fea301e14838c9825cdba5b209990968fdc6f8010c7"

reddit.com. 3578 IN TXT "twilio-domain-verification=5e37855d7c9445e967b31c5e0371ebb5"

reddit.com. 3578 IN TXT "v=spf1 include:amazonses.com include:_spf.google.com include:mailgun.org include:19922862.spf01.hubspotemail.net ip4:174.129.203.189 ip4:52.205.61.79 ip4:54.172.97.247 ~all"

reddit.com. 3578 IN TXT "614ac4be-8664-4cea-8e29-f84d08ad875c"

reddit.com. 3578 IN TXT "MS=ms71041902"

reddit.com. 3578 IN TXT "apple-domain-verification=qC3rSSKrh10DoMI7"

reddit.com. 3578 IN TXT "atlassian-domain-verification=aGWDxGvt+oY3p7qTWt5v2uJDVJkoJAeHxwGqKmGQLMEsUXUJJe/Pm/k+GGNPpn6M"

reddit.com. 3578 IN TXT "atlassian-domain-verification=vBaV6PXyyu4OAPLiQFbxFMCboSTjoR/qxKJ2OlpI46ZEpZL/FVTIfMlgoM5Hy9eY"

reddit.com. 3578 IN TXT "box-domain-verification=95c33f4ee4b11d8827190dbc5371ca7df25b961019116e5565ce4aa36de9be3a"

reddit.com. 3578 IN TXT "docusign=6ba0c5a9-5a5e-41f8-a7c8-8b4c6e35c10c"

reddit.com. 3578 IN TXT "google-site-verification=0uv13-wxlHK8FFKaUpgzyrVmL1YdNYW6v3PupLdw3JI"

reddit.com. 3578 IN TXT "google-site-verification=oh_YJE560y0e6FHP1RT7NIjyTlBhACNMvD2EgSss0sc"

reddit.com. 278 IN AAAA 2a04:4e42:200::396

reddit.com. 278 IN AAAA 2a04:4e42:400::396

reddit.com. 278 IN AAAA 2a04:4e42:600::396

reddit.com. 278 IN AAAA 2a04:4e42::396

reddit.com. 86378 IN CAA 0 issue "digicert.com; cansignhttpexchanges=yes"

Received 1838 bytes from 10.220.0.1#53 in 15 msAs you can see, an absolutely enormous amount of information was pulled. That’s because using -a tells host to pull all of the records it can from it’s target.

You can also perform zone transfers:

[~]$ host -l reddit.com

;; Connection to 123.456.78.9#53(123.456.78.9) for reddit.com failed: connection refused.

;; Connection to 123.456.78.1#53(123.456.78.1) for reddit.com failed: connection refused.And it seems that the default nameserver (123.456.78.9) didn’t allow us to do this.

Nslookup

This tool functions fairly similarly to host and dig but has an optional interactive mode. This is useful for when you want to frequently options such as query types and nameservers without retyping the name of the command all over again.

Here’s a quick example:

[~]$ nslookup

> set type=NS

> microsoft.com

Server: 123.456.78.9

Address: 123.456.78.9#53

Non-authoritative answer:

microsoft.com nameserver = ns4-39.azure-dns.info.

microsoft.com nameserver = ns1-39.azure-dns.com.

microsoft.com nameserver = ns2-39.azure-dns.net.

microsoft.com nameserver = ns3-39.azure-dns.org.

Authoritative answers can be found from:

> server ns1-39.azure-dns.com

Default server: ns1-39.azure-dns.com

Address: 150.171.10.39#53

Default server: ns1-39.azure-dns.com

Address: 2603:1061:0:10::27#53

> set type=MX

> microsoft.com

Server: ns1-39.azure-dns.com

Address: 150.171.10.39#53

microsoft.com mail exchanger = 10 microsoft-com.mail.protection.outlook.com.To access interactive mode, I ran nslookup without any arguments. From there I set the query type to NS to look up microsoft.com‘s nameservers, then used one of their nameservers to look up their mail servers.

As you can see, most of the commands I typed were only one or two words long. For this reason, I like nslookup for poking around if I’m not necessarily sure what I’m looking for and need to frequently update my commands.

It’s important to note that these three tools (dig, host, nslookup) function very similarly. So, I encourage you to try all of them, use them interchangeably, and read the man pages for each one. They each have their strengths and weaknesses. The one you choose depends on your situation and preferences.

Subdomain Enumeration

Subdomain enumeration is the process of finding as many subdomains associated with a domain as possible. This is an important process of DNS enumeration as it expands our attack surface even further. You can also apply the techniques described previously on the subdomains you find to make your enumeration even more effective.

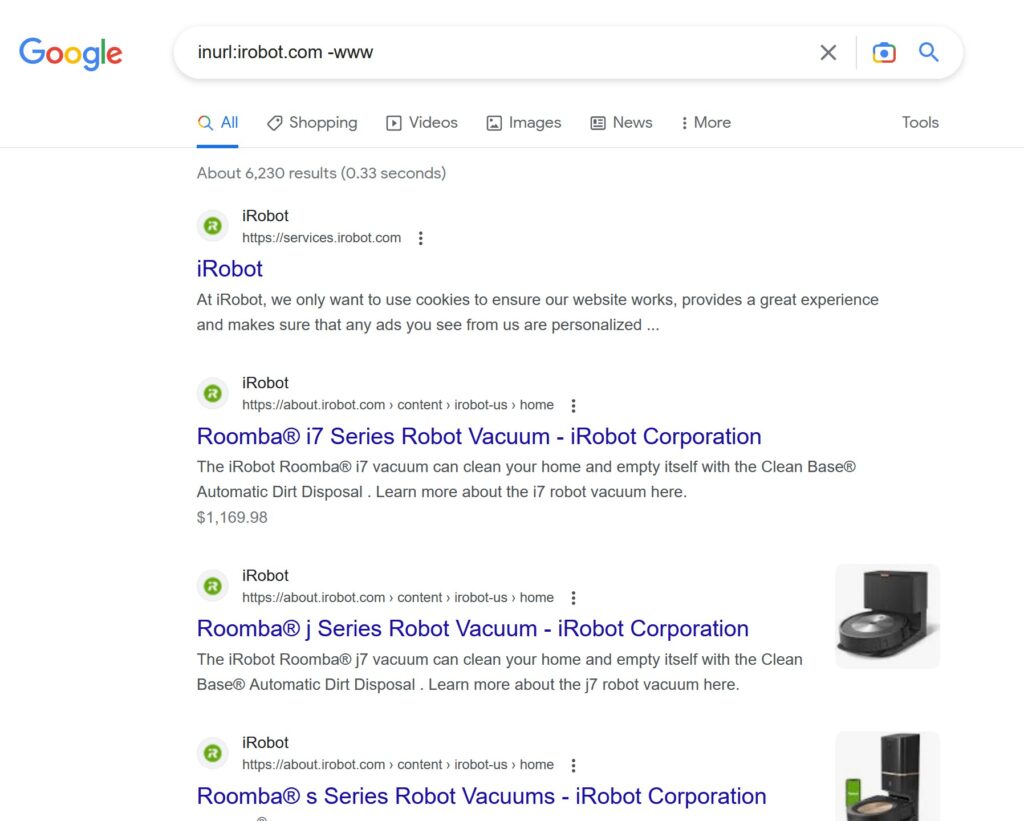

Most modern search engines can be a useful tool for subdomain enumeration. If you read one of my earlier posts about Google Dorking, you may already be familiar with the technique I’m about to describe.

Google makes subdomain enumeration a snap with the inurl parameter:

Using inurl and the domain name, irobot.com, I was able to find numerous subdomains. I also used -www to tell Google to exclude search results containing www.

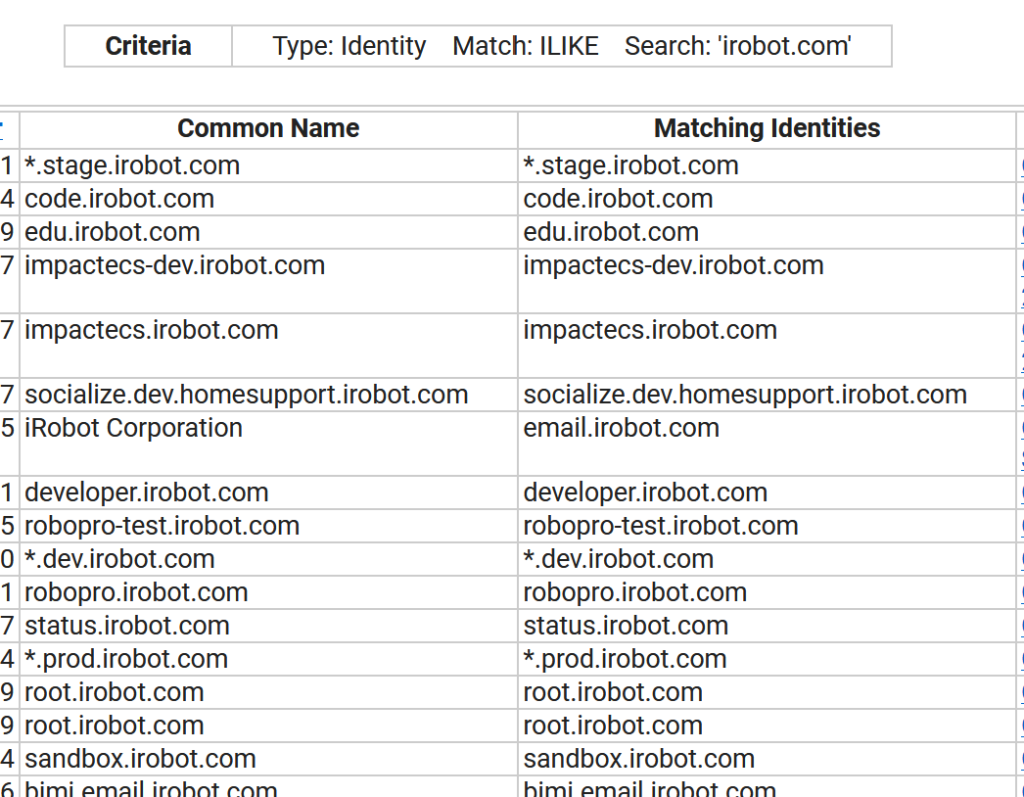

Another powerful tool for subdomain enumeration is the Certificate Search tool:

%.irobot.comThe query I used to pull all of these results was %.irobot.com, where the % symbol was a wild card. This means that results with anything ending with “.irobot.com” will be a part of the search results.

Combining these techniques is a powerful way of discovering subdomains that give you an edge by providing you with more information.

Automated Techniques

Now that you know some basic (but powerful) techniques for enumerating subdomains, its time to automate the process.

There’s tons of tools out there that do all of these steps (and more) to provide you with as much information associated with a domain name as possible. One popular one is dnsenum. As described in its man pages dnsenum can perform:

nslookup, zonetransfer, google scraping, domain brute force (support also recursion), whois ip and reverse lookups.Here’s what I was able to pull by pointing this tool at burgerking.com:

[~]$ dnsenum burgerking.com

dnsenum VERSION:1.2.6

----- burgerking.com -----

Host's addresses:

__________________

burgerking.com. 37 IN A 99.84.66.7

burgerking.com. 37 IN A 99.84.66.86

burgerking.com. 37 IN A 99.84.66.37

burgerking.com. 37 IN A 99.84.66.51

Name Servers:

______________

udns1.cscdns.net. 28800 IN A 204.74.66.1

udns2.cscdns.uk. 13091 IN A 204.74.111.1

Mail (MX) Servers:

___________________

ASPMX2.GOOGLEMAIL.com. 293 IN A 64.233.171.27

ALT2.ASPMX.L.GOOGLE.com. 293 IN A 142.250.152.27

ALT1.ASPMX.L.GOOGLE.com. 293 IN A 64.233.171.27

ASPMX.L.GOOGLE.com. 292 IN A 142.250.141.26

ASPMX3.GOOGLEMAIL.com. 293 IN A 142.250.152.27

Trying Zone Transfers and getting Bind Versions:

_________________________________________________

Trying Zone Transfer for burgerking.com on udns1.cscdns.net ...

AXFR record query failed: REFUSED

Trying Zone Transfer for burgerking.com on udns2.cscdns.uk ...

AXFR record query failed: REFUSED

Brute forcing with /usr/share/dnsenum/dns.txt:

_______________________________________________

www.burgerking.com. 86400 IN CNAME prod-bk-web.com.rbi.tools.

prod-bk-web.com.rbi.tools. 60 IN A 13.33.21.112

prod-bk-web.com.rbi.tools. 60 IN A 13.33.21.119

prod-bk-web.com.rbi.tools. 60 IN A 13.33.21.10

prod-bk-web.com.rbi.tools. 60 IN A 13.33.21.51I cut the scan short but you can see it was able to pull some useful servers (as well as their IP addresses), find some domains, and attempted to do a zone transfer and figure out the DNS server’s bind version.

Other great tools include fierce, dnsrecon, and sublist3r (for enumerating subdomains). I encourage you to try them all out and see what tools work for you. There are also tons of opensource tools out there that I haven’t mentioned that you should try as well!

Now that you’ve seen a fantastic tool that formats everything you might need beautifully with color-coding, you may be asking yourself: “Why even bother with manual testing in the first place?”

While these tools are extremely efficient, they may not be a one line solution for all of your needs. It’s important when enumerating to supplement your automated information gathering with manual gathering.

Manual enumeration is extremely flexible, allowing you to poke around at every angle you can think of and dig deeper than some automated scripts. It’s also worth noting that these automated scripts generate a ton of traffic. So, in a scenario where stealth is required, it may be more appropriate to manual test to fly under the radar.

Conclusion

DNS enumeration is a critical step in the process of analyzing your target. When executed correctly, it can be used to expose a wealth of information. The more information you have on a target, the more effective your penetration test will be.

I only covered the basics to give you a starting point. I highly encourage you to look at the manual pages (with the man command, arguably the best UNIX command) to learn the ins and outs of these tools so you can make the most out of them. At the end of the day, these tools are simply lines of code–it’s up to you to make them useful.

Remember, this information is all public, so feel free to practice on your own (you definitely should) and see what you can dig up. Just be careful when using the brute-force tools against servers you don’t own (again read the man pages so you know what you’re doing) and don’t use any of the information you gather without permission.

That’s all and happy hunting! In the next post, I’m going to be talking about scanning with nmap so stay tuned for that!

References

https://resources.infosecinstitute.com/topic/dns-enumeration-techniques-in-linux/